1. As The Co2 Level Increases Up To 600 Ââµmol Mol-1, How Does Ragweed Pollen Production Change?

Trends in Solid Waste matter Management

The world generates 2.01 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste annually, with at least 33 per centum of that—extremely conservatively—non managed in an environmentally safe manner. Worldwide, waste matter generated per person per day averages 0.74 kilogram but ranges widely, from 0.11 to 4.54 kilograms. Though they only business relationship for 16 pct of the world'south population, loftier-income countries generate about 34 percent, or 683 one thousand thousand tonnes, of the globe's waste.

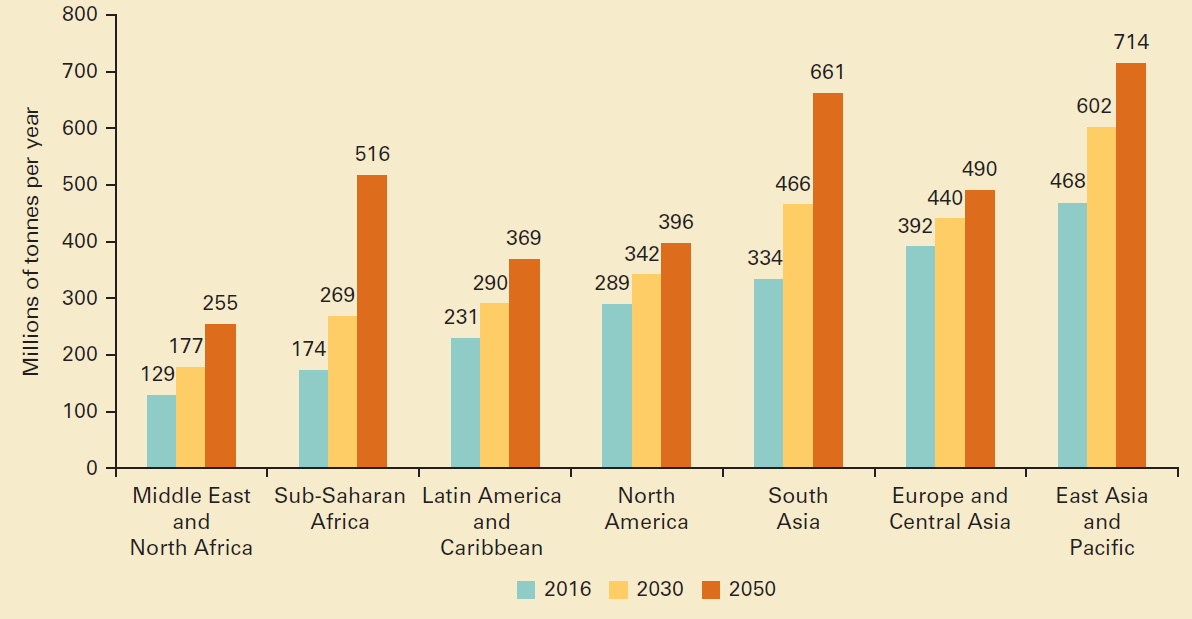

When looking forward, global waste is expected to grow to iii.40 billion tonnes by 2050, more than than double population growth over the aforementioned catamenia. Overall, there is a positive correlation between waste generation and income level. Daily per capita waste matter generation in loftier-income countries is projected to increase by 19 percent past 2050, compared to low- and heart-income countries where it is expected to increase by approximately 40% or more. Waste generation initially decreases at the lowest income levels and so increases at a faster rate for incremental income changes at low income levels than at high income levels. The total quantity of waste generated in low-income countries is expected to increase by more than than 3 times past 2050. The E Asia and Pacific region is generating most of the earth'due south waste, at 23 percent, and the Middle East and North Africa region is producing the to the lowest degree in accented terms, at vi percentage. However, the fastest growing regions are Sub-Saharan Africa, South asia, and the Middle Due east and North Africa, where, by 2050, total waste generation is expected to more than triple, double, and double respectively. In these regions, more than half of waste is currently openly dumped, and the trajectories of waste growth will have vast implications for the environment, health, and prosperity, thus requiring urgent activeness.

Projected waste material generation, past region (millions of tonnes/year)

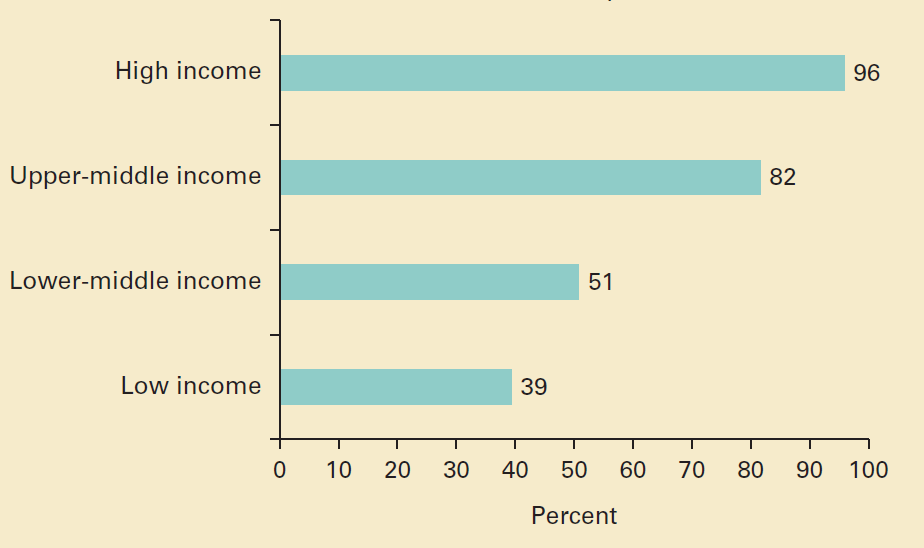

Waste collection is a disquisitional footstep in managing waste matter, even so rates vary largely past income levels, with upper-heart- and high-income countries providing nearly universal waste collection. Depression-income countries collect about 48 percent of waste material in cities, but this proportion drops drastically to 26 pct exterior of urban areas. Across regions, Sub-Saharan Africa collects well-nigh 44 percent of waste while Europe and Key Asia and Due north America collect at least ninety pct of waste.

Waste matter drove rates, by income level (per centum)

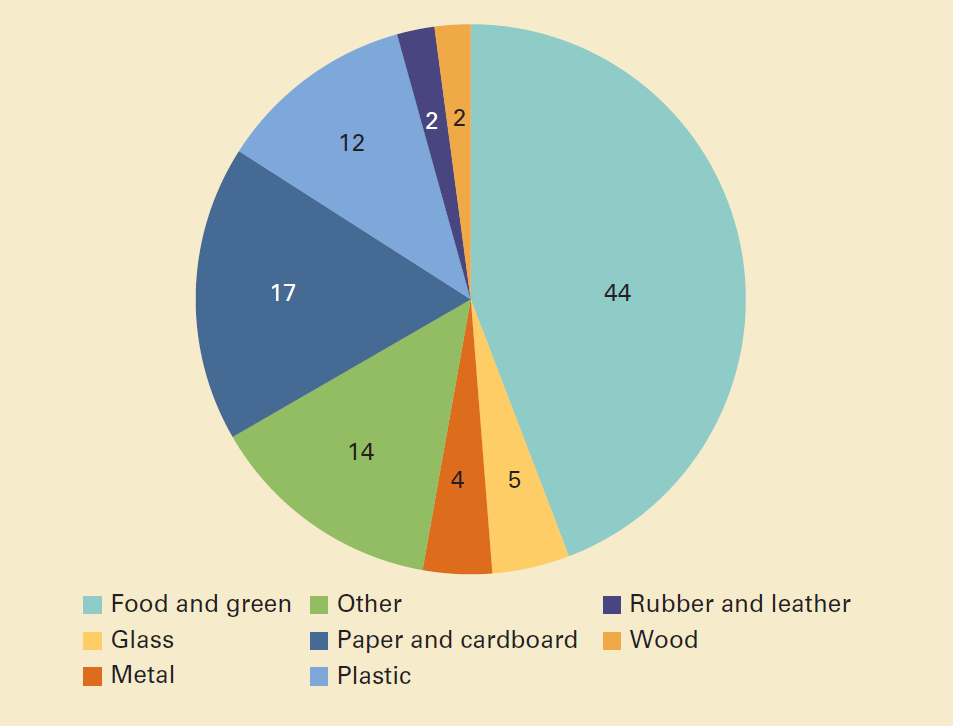

Waste material composition differs across income levels, reflecting varied patterns of consumption. Loftier-income countries generate relatively less nutrient and light-green waste, at 32 per centum of total waste, and generate more than dry waste that could be recycled, including plastic, paper, cardboard, metal, and glass, which account for 51 percent of waste. Heart- and low-income countries generate 53 percent and 57 pct food and green waste, respectively, with the fraction of organic waste product increasing equally economic development levels decrease. In depression-income countries, materials that could be recycled account for only 20 per centum of the waste material stream. Beyond regions, at that place is not much diversity within waste streams beyond those aligned with income. All regions generate about fifty percentage or more organic waste product, on average, except for Europe and Central Asia and North America, which generate higher portions of dry out waste.

Global waste composition (percent)

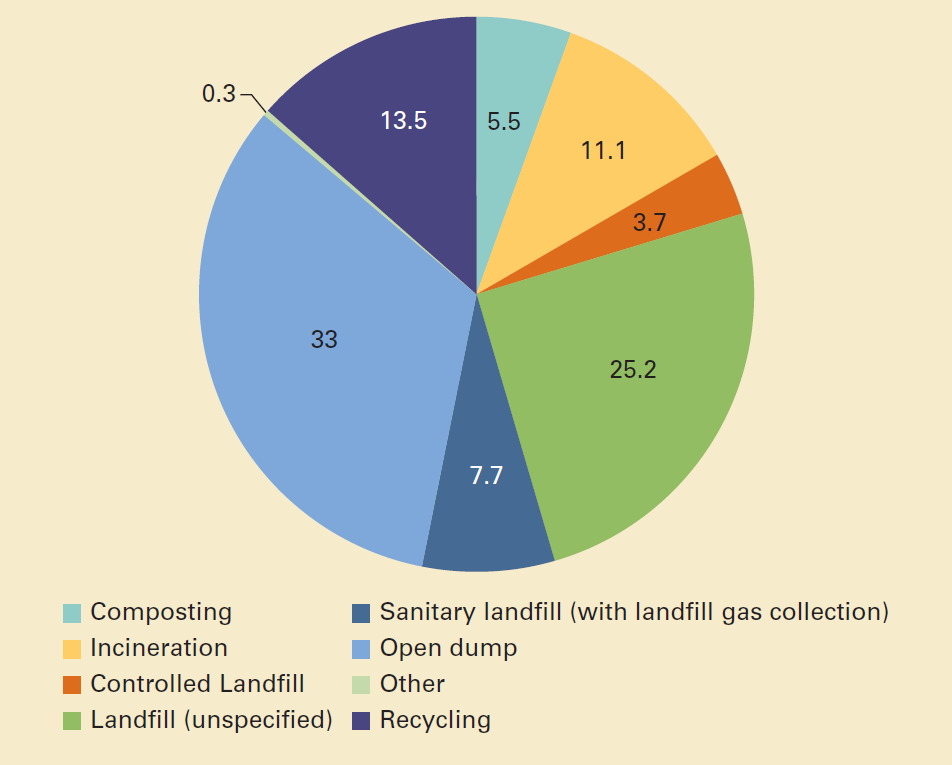

It is a frequent misconception that engineering is the solution to the problem of unmanaged and increasing waste matter. Technology is not a panacea and is unremarkably only one factor to consider when managing solid waste. Countries that advance from open dumping and other rudimentary waste management methods are more likely to succeed when they select locally appropriate solutions. Globally, most waste is currently dumped or disposed of in some form of a landfill. Some 37 per centum of waste is disposed of in some form of a landfill, 8 percent of which is disposed of in sanitary landfills with landfill gas collection systems. Open dumping accounts for virtually 31 pct of waste product, nineteen percentage is recovered through recycling and composting, and eleven percent is incinerated for final disposal. Adequate waste disposal or treatment, such as controlled landfills or more stringently operated facilities, is about exclusively the domain of high- and upper-middle-income countries. Lower-income countries more often than not rely on open dumping; 93 percent of waste matter is dumped in low-income countries and merely ii percent in high-income countries. Three regions openly dump more than half of their waste matter—the Middle E and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southern asia. Upper-middle-income countries have the highest percentage of waste matter in landfills, at 54 percent. This charge per unit decreases in high-income countries to 39 per centum, with diversion of 36 pct of waste product to recycling and composting and 22 percent to incineration. Incineration is used primarily in high-capacity, high-income, and country-constrained countries.

Global treatment and disposal of waste (percent)

Based on the volume of waste matter generated, its limerick, and how it is managed, it is estimated that one.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent greenhouse gas emissions were generated from solid waste treatment and disposal in 2016, or 5 per centum of global emissions. This is driven primarily by disposing of waste product in open up dumps and landfills without landfill gas collection systems. Nutrient waste accounts for virtually l% of emissions. Solid waste product–related emissions are anticipated to increase to ii.38 billion tonnes of CO2-equivalent per year by 2050 if no improvements are fabricated in the sector.

In most countries, solid waste matter management operations are typically a local responsibility, and nearly seventy percent of countries accept established institutions with responsibleness for policy development and regulatory oversight in the waste sector. About ii-thirds of countries take created targeted legislation and regulations for solid waste matter management, though enforcement varies drastically. Directly primal government involvement in waste service provision, other than regulatory oversight or fiscal transfers, is uncommon, with about seventy percent of waste matter services being overseen directly by local public entities. At to the lowest degree half of services, from primary waste material collection through treatment and disposal, are operated by public entities and about i-3rd involve a public-individual partnership. Yet, successful partnerships with the private sector for financing and operations tend to succeed only under certain conditions with appropriate incentive structures and enforcement mechanisms, and therefore they are not always the ideal solution.

Financing solid waste matter management systems is a pregnant claiming, even more so for ongoing operational costs than for majuscule investments, and operational costs demand to be taken into account upfront. In loftier-income countries, operating costs for integrated waste direction, including col-lection, transport, handling, and disposal, mostly exceed $100 per tonne. Lower-income countries spend less on waste operations in absolute terms, with costs of about $35 per tonne and sometimes college, but these countries experience much more difficulty in recovering costs. Waste management is labor intensive and costs of transportation lone are in the range of $20–$l per tonne. Cost recovery for waste services differs drastically across income levels. User fees range from an average of $35 per year in depression-income countries to $170 per yr in high-income countries, with full or near full price recovery being largely limited to high-income countries. User fee models may be fixed or variable based on the type of user beingness billed. Typically, local governments cover nigh fifty pct of investment costs for waste systems, and the remainder comes mainly from national government subsidies and the private sector.

Source: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html

Posted by: jacobsthadet.blogspot.com

0 Response to "1. As The Co2 Level Increases Up To 600 Ââµmol Mol-1, How Does Ragweed Pollen Production Change?"

Post a Comment